My German grandmother did not own a lot of books. In fact, she only had a range of about two shelves. One of these shelves was filled with a complete collection of all of Goethe’s and Schiller’s works, two of the most significant German writers. The other shelf was filled with a complete collection of the encyclopedia Brockhaus. Back then it consisted of 28 books – 25 volumes with keywords and 3 volumes with a dictionary. And I also remember: Whatever we wanted to know, at some point the Brockhaus entered the stage.

Today, the encyclopedia does not exist in my life anymore. When my grandmother died, my parents gave it away to a local library. And even if I wanted to acquire it again on paper, I couldn’t. The publishing house behind the books does not even exist anymore. The only appearance of all the information collected by generations and united between a number of book covers can now be found online – behind a paywall. So I and many more make the decision to access all the information the human race has probably ever acquired through a website that offers this information for free. Google and Wikipedia will help me find my way around.

Since all of our information is available for everyone online, everybody has access to the full cornucopia. It seems it has become easier to find even the weirdest piece of information. And this collection grows immensely ever day, every minute, every second. So now that we have a whole research department at the fingertips of our hands, are we all becoming super brains?

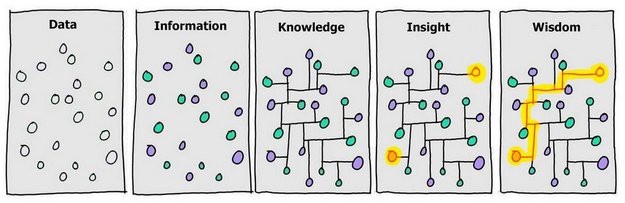

Not quite. That would require that we know how to turn information into knowledge. However, herein lies the crux. The words, although often used interchangeably, have completely different characteristics. In fact they build on each other like in a pyramid.

In the beginning there is pure, raw and dry data. It can be a fact, a symbol, a sign. It has no meaning on its own. Let’s look at our next book shopping experience as an example. You go into a book store, pick up a random book, and read the title. It reads “How to acquire wisdom”.

Information is what we get, when we refine data. When we put it in some form of context. For example, there is a huge difference in the context, if we pick up our book in the secion of “Education” or “Love stories”. This book will probably have very different contents depending on where we pick it up! The data gets context and with that a meaning.

Just because we have an information does not automatically imply that we know something. Knowledge rises from putting that information that we just got into a pattern. It allows us to add meaning onto the information and enables us to make assumptions. Let’s say we pick the book up while roaming the education section. Taken into account that our book has the title “How to acquire wisdom” and is found in the “Education” section, we can make assumptions about the content of the book. It probably is a non-fiction book, that teaches us something about learning.

Now we know. But what do we do with our knowledge now? That’s where wisdom comes into play. We know the facts, we know the patterns. Wisdom enables us to make the right prediction because we know the “Why” behind the model.

“You can’t expect somebody to become a biologist by giving them access to the Harvard University biology library and saying, ‘Just look through it.’”, Linguist and philosopher Noam Chomsky says. “The person who wins the Nobel Prize in biology is not the person who read the most journal articles and took the most notes on them. It’s the person who knew what to look for. Cultivating that capacity to seek what’s significant, always willing to question whether you’re on the right track, that’s what education is going to be about, whether it’s using computers and internet, or pencil and paper and books.”

And yet, the fairytale of “data as the new gold” makes its rounds in the board rooms. We know how to dig for and collect data. But we seem to stop there and think that now that we lifted the treasure from the depths of the earth the work is done and we are rich. Open Source projects ride the wave a bit further. If only all the data and information were accessible for everyone we would pave the way for a better society.

The amount of information is already unsurmountable. But in fact and paradoxically, it seems we are becoming less and less equipped to put data into a context and information into a pattern. Recent crisis situations show that we are great at throwing data into the arena, but we are really bad at using the data to build weapons to fight problems on a huge societal scale. And the problem gets bigger and bigger the more data, especially counteracted, we acquire.

So why not give in, trust the numbers and take one of the first search results available. It has the most views. It seems measurably an important piece of information. Putting a number on information is easy.

When we look for information, we have a question. We don’t have to put it in a question form, but somewhere in our considerations there is a question involved. The Brockhaus was fairly static. The pages didn’t look different with every search query that I approached it with.

Google is different. Search engines don’t give you the most correct answers, they give you the most favourable. And favourable, in their vocabulary, means that piece of information that sells their own services best – through ads and time spent on the page, for example. The result you get is solely statistical – and through that highly fluid. And furthermore, because we can ask Google anything and the search engine does not have an interest in losing our attention, they provide a result for everything. The concept of “unknowable” is not a thing Google accepts. Even for the most complex question we get a quick hit, based on your former search history and your clicks. Which in return makes it so difficult to agree on a common base of information. Nobody sees exactly the same search result.

And if we can’t agree on the same base of information, how should we even start to agree on common knowledge? With all the big amount of information surrounding us we need help to put the data and information into a context. Mostly, there are two big players who try to do that. Contestant Number 1: Science. Although we also find exceptions to the rule in this corner, scientific knowledge is the knowledge that currently has the most evidence to back it. Contestant Number 2: Media and Journalism. And although there are brilliant journalists out there who do an amazing job, media is run by the rules of attention economy – The winner is the opinion that unites the biggest masses behind them.

So when we rely on what we google and what we read in the media, our stream of information is highly led by their principle of the biggest numbers. But is that really what we want to consider knowledge?

So how do we learn to know again? First of all, we need to figure out: What is really the question that we want to find an answer to? Second, we need to be aware of the difference. Having data is not the same as being informed. And having information is not necessarily the same as knowing something. But we can bridge the gap that by telling stories.

Stories are a great way to transport meaning to people. We have been telling stories throughout human history to transport individual experiences and shape our world as we know it today. This is, how we transport experiences since the beginning of speech. Stories are our way to make sense of our findings.

Data tells us what happens. Stories allow us to ask and tell, why! What are the patterns and implications? And what does all of that really mean? Humans are notoriously bad at comprehending the meaning of numbers. Without context they don’t give us anything to grasp, what is really going on. Stories can help us make sense of the data, as they also allow us to fill the dry data with life. With meaning and a feeling we can rely to.

My grandmother was not a stupid woman. Because in her own way, she had a lot of knowledge. She didn’t know all the facts and figures. Neither did she have a whole library available. She couldn’t pick up her smartphone and just google them. But two generations of gains in information and access to it don’t automatically make me a smarter woman than my grandmother, either.

What made our conversations so interesting were the stories she could tell. I remember for example, how she filled the information I got in my history lessons with the life of her own lived stories. Probably we would be a good team now. I could look up the information and she could tell a story around it. A story from her life or a story she was told throughout her life. And who knows, maybe we would be the team that could turn information into knowledge for somebody, by telling our story.